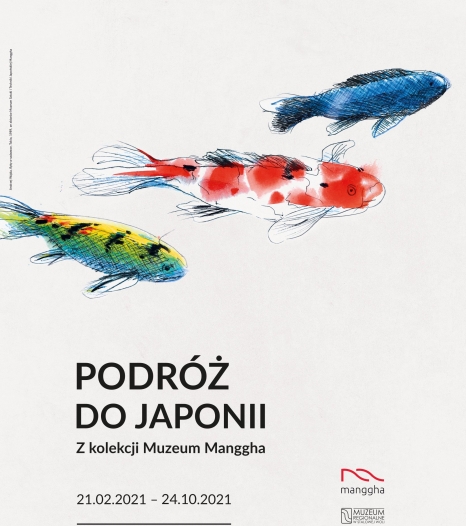

Podróż do Japonii

21.02-24.10.2021 PODRÓŻ DO JAPONII. Z kolekcji Muzeum Manggha

Galeria Malarstwa Alfonsa Karpińskiego Stalowa Wola, ul. Rozwadowska 12

In February 2021, the Regional Museum in Stalowa Wola will take its viewers on an extraordinary journey to Japan, where they will see captivating landscapes and architecture, meet interesting people, learn about their customs, daily life and favourite dishes. They will get closer to this fascinating country through drawings, photographs, sculptures, woodcuts, which are signs of admiration and reflection.

The exhibition has been prepared in cooperation with the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Krakow. Its narrative is built up by drawings by Andrzej Wajda and reportage-documentary photographs from the 1930s. Ze’ev Aleksandrowicz and Franz Stoedtner, Alisa Lahusen’s objects inspired by lacquer, a traditional Japanese technique, and Hiroshige’s woodcuts, and complemented by contemporary images of Japanese people in Hiroha Kikai’s photographs.

‘Even the longest journey begins with the first step’. The exhibition Journey to Japan at the Regional Museum in Stalowa Wola is nothing less than the beginning of this journey.

Scenario and arrangement: Dr Anna Król

Graphic interventions: Przemysław Wideł

Ze’ev Wilhelm Aleksandrowicz (1905-1992), amateur photographer, was born into a well-known Jewish family of paper industry entrepreneurs (running the company ‘R. Aleksandrowicz and Sons’). In 1934 he travelled around the world, and from 29 November to 23 December he was in Japan, where he took more than two thousand photographs on black-and-white small-format film with a Leica camera. The Manggha Museum received one hundred and forty of them. Aleksandrowicz’s Japanese photographs are an interesting record of the clash between West and East, the meeting of different cultures and different people. Landscapes, architectural monuments, accidentally encountered people, poor and rich, in the theatre, at the train and underground station, on the road and in the temple, children, students – these are a record of a world that no longer exists today, a photographic ukiyoe.

Franz Stoedtner (1870-1945), art historian and publisher, is considered one of the forerunners of documentary photography. In 1895, he founded the Institut für wissenschaftliche Projection in Berlin, one of the first commercial institutions to distribute photographs for scientific purposes. Images sold in the form of glass slides were particularly popular as teaching aids at German universities.

Stoedtner undertook a project on an unusual scale for the time – his archive contained more than two hundred thousand photographs. They depicted various parts of the world and were divided into sets on various themes: near and far countries, art history, technology. One such set depicted Japan.

The photographs were taken on two of Japan’s four main islands, Kiusiu and Honsiu, most likely in late 1936 and early 1937. They show the country seventy years after the epochal event of the Meiji Restoration: the fall of the military regime of the Tokugawa family and the Emperor’s regaining of power, the opening of borders that had been closed for over two hundred and fifty years, and the clash with Western culture – the confluence of the traditional with the modern.

The years that followed the Meiji era were marked by a modernisation of the country carried out on an unprecedented scale. For Japan, it was a time of great social tension: attempts to reconcile native customs with those coming from the West, the need to redefine one’s own identity and take a stand against a changing, troubled world. The 1920s and 1930s also marked the prelude to Japan’s extraordinary militarisation. And while there is little indication of this – the lens focuses on festivities, customs and beautiful sights – the photographs depict the country on the eve of war.

One of the most valuable parts of the Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology’s collection is a unique collection of works on paper – sketches and drawings – by Andrzej Wajda (1926-2016). Among the most interesting are those from his travels to Japan. The director visited the country seven times – in 1970, 1980, 1987, 1989, 1992, 1993 and 1996 – including six times with his wife, Krystyna Zachwatowicz-Wajda. During each trip, he took notes, sketched, remembering the most significant elements of a different, foreign, culture, of an unknown country. A country that in time became ‘Their Japan’.

In the fourteen notebooks and sketchbooks we find a ‘pictorial’ story not only about Japan, but also, or perhaps above all, about the painter-director, his artistic preferences, inspirations and discoveries. As we know, sketching for Andrzej Wajda was a form of communication with the world, a function of memory. We present the Japanese sketches chronologically, according to the rhythm of the Director’s travels. This arrangement seems to illustrate perfectly the successive stages of cognition, admiration and reflection on another culture and art.

Hiroh Kikai (1945-2020), one of Japan’s most important photographic artists. For more than forty years, he has photographed people he met in Asakusa, Tokyo, always in the same way: in daylight, against the red wall of the Senjōji Buddhist temple, he would position a person, asking them to tell who they are and what they do – this later formed the basis of the photo’s description. He always devotes the same amount of time to each person – 10 minutes. The transience of the moment is juxtaposed with reality.

I’ve been photographing people since I took up photography. I usually accost strangers somewhere in the city centre, ask for permission and take their picture. The rules are simple. Although I choose unusual characters, I try to avoid looking ‘down’ or glorifying them. That’s why my portraits are not just ordinary faces of the photographed ‘subjects’, they are faces full of expression, emanating a charm that is difficult to define (Hiroh Kikai).

Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858), along with Utamara and Hokusai, ranks among the greatest ukiyo-e artists, those who decisively influenced Western art of the 19th and 20th centuries. In addition to woodcuts, he was involved in painting, interested in the various Japanese schools as well as Western art; he was particularly fascinated by the modern perspective, which fundamentally enriched his works.

Although Hiroshige came from a samurai family, he identified with the bourgeois culture of Edo, so he easily depicted its characteristic elements, showing images of beautiful women, portraits of actors, theatre scenes. Nevertheless, he became known primarily as the creator of landscape series such as Fifty-three Stations on the Tōkaidō Road, Eight Views of Ōmi Province, and One Hundred Views of Famous Places in Edo. He masterfully depicted the landscape in different seasons of the year and day, in the changing effects of the weather. He used innovative compositional tricks, unconventional solutions of space, and an original way of framing fragments of reality. These naturalistic yet atmospheric prints create an unusual and poignant vision of Japan. Around ten thousand of his works are known.

Japanese lacquer (urushi 漆) is created from a resin extracted from the tree Toxicodendron vernicifluum (lac sumac), which grows on the south-eastern coasts of Asia. It is used in the production of arts and crafts, as well as tableware, everyday utensils and furniture. The characteristics of the finished product are strength and resistance to water, alcohol, fats and high temperatures. As well as serving a protective function for the object made from it, laka can be used for decoration. The Manggha Museum houses many items of Japanese handicraft made using this technique, as well as examples of its use in contemporary art, including the work of Aliska Lahusen, a Polish artist living and working in France.

Laka is an interesting technique and medium for many contemporary artists. In the Japanese tradition, mirrors are associated with darkness because they retain and store light. I was looking for a medium that I could use to sort of write down states of consciousness, layer by layer. It was also essential for me to be able to play with colour as well as light and transparency. It seemed to me that traditional lacquer would allow this sense of existence to be conveyed in this way, and this was the path I chose (Aliska Lahusen).