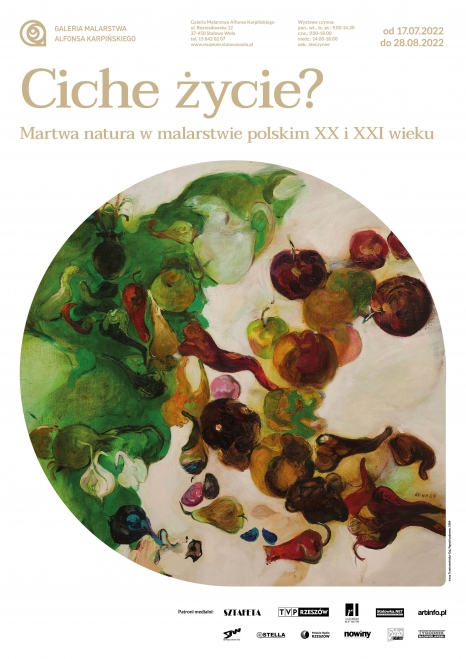

Silent life? Still life in 20th and 21st century Polish painting

17.07-28.08.2022, Silent life? Still life in 20th and 21st century Polish painting

exhibition venue: Alfons Karpinski Gallery of Painting, 12 Rozwadowska St. Exhibition curator Dr Anna Król

The Regional Museum in Stalowa Wola invites you to a new exhibition presenting the phenomenon of still life in Polish painting of the last one hundred and twenty years. Over 80 works by 23 artists are presented: Olga Boznańska, Dorota Ćwieluch-Brincken, Tadeusz Jackowski, Ewa Kierska-Hoffmannowa, Roman Kramsztyk, Katarzyna Makieła-Organista, Janusz Matuszewski, Józef Pankiewicz, Kazimierz Podsadecki, Marek Przybył, Mirosław Sikorski, Barbara Skąpska, Edyta Sobieraj, Jan Spychalski, Henryk Stażewski, Witold Stelmachniewicz, Irena Trzetrzewińska, Romuald Kamil Witkowski, Czesław Wdowiszewski, Szymon Wojtanowski, Witold Wołczaski, Jan Wydra and Stanisław Zalewski.

In the 19th century, in accordance with the prevailing academic hierarchy of subjects, still life – a sign of bourgeois culture, although it had existed since Pompeian times and experienced its heyday in the modern era – occupied a secondary position for a very long time, with a primarily decorative function. It was not until the Impressionists and Paul Cezanne that it became a fully autonomous genre of painting. Its name, coined in the circle of French academics (nature morte), functions in Polish and Italian. By contrast, in the 17th century, Dutch painters began to use the term stilleven, literally ‘quiet life’, to describe compositions depicting stationary objects, ‘models’. Over time, the term changed its original meaning, becoming a metaphor, a poetic sign.

In Polish painting, interest in still life as an independent artistic subject appears in the 1890s. Young Polish artists discovered its potential possibilities and treated it as a pretext not only for formal experiments, but also for encoding symbolic content. Among the objects building up the still lifes, we find Japanese props – porcelain vases and Buddhist altars (Józef Pankiewicz), as well as bouquets of flowers (Olga Boznańska). Juxtaposed in simple or complex arrangements, they create sophisticated, sometimes ambiguous compositions. In the interwar period, almost all artists took up this theme, creating both economical compositions with a precise, almost constructivist structure (Romuald K. Witkowski, Stanisław Zalewski) and expressive, painterly ones (Jan Wydra, Roman Kramsztyk). There were also magical still lifes (Jan Spychalski). This geometrising line was continued after the war by, among others, Kazimierz Podsadecki and Henryk Stażewski.

In the second half of the 20th and into the 21st century, still life is omnipresent. When looking at the work of artists associated with the Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow, one can clearly see a fascination with this subject. Although they use a variety of visual languages, they constantly reinterpret this apparently well-known genre. The painting compositions of Ewa Kierska-Hoffmann, Irena Trzetrzewińska or Katarzyna Makieła-Organista (dedicated to such masters of ‘quiet life’ as Georg Flegel, Jan van Kessel or Francisco de Zurbarán), create their own microcosmos, delude with reality, delight and induce contemplation. Dorota Ćwieluch-Brincken’s paintings, on the other hand, are an attempt to bring order to the chaos of reality by giving found, inconspicuous objects – shells or stones – a special meaning in a sophisticated painting space. Edyta Sobieraj, on the other hand, creates poetic, substantial worlds constructed on the everyday experience of her immediate surroundings: her studio, her home. It should be remembered that still lifes often encoded symbolic content. The objects depicted in the paintings were inert, and when juxtaposed in a particular order, they constituted a specific cultural text. Thus, juxtaposing the paintings of Jan Matuszewski, Szymon Wojtanowski and Witold Stelmachniewicz, one can see a common vanitas, regardless of the prop used: a skull, a vessel, a pomegranate. This theme is complemented in the exhibition by Mirosław Sikorski’s paintings from the Enfleurage series, entering into an interesting dialogue with Alfons Karpiński’s roses. Regardless of the adopted language of painting, the paintings presented at the exhibition seem to be the very essence of painting.

The exhibition features works on loan from artists, collectors and museum collections (National Museum in Krakow, National Museum in Warsaw, District Museum in Toruń, Art Museum in Łódź, Manggha Museum of Japanese Art and Technology in Krakow).

– Anna Król

– Scenario and artistic arrangement of the exhibition: Dr Anna Król Coordination

– on the part of the Regional Museum: Monika Kuraś